Convergent assembly

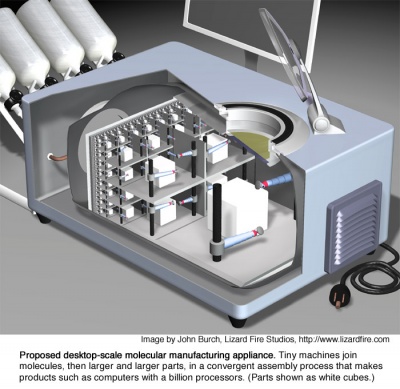

In advanced atomically precise manufacturing systems convergent assembly is the general process of taking small parts and putting them together to bigger parts and then taking those bigger parts and putting them together to even bigger parts and so on.

Convergent assembly must not be confused with exponential assembly (a concept for bootstrapping AP manufacturing).

Contents

Motivations for convergent assembly

- Avoiding unnecessary disassembly when reconfiguring already produced products in a way that just swaps big chunks.

- Allowing to assemble unstable overhangs or impossible undercuts without scaffolds. (stalactite like structures)

- The possibility to keep everything in a vacuum/cleanroom till the final product release - this should not be necessary and may decrease the incentive for the creation of systems that are capable of recycling.

- Nontrivial effects on speed.

General

In an advanced gem-gum-factory the convergent assembly levels can be identified with the abstract assembly levels. Note that those are not tied to any specific geometric layout.

Stacking those levels to layers as a concrete implementation is a good first approximation (especially in the mid range size levels where scale invariant design holds for a decent range of orders of magnitudes) it creates a nanofactory which is practical and conveniently also reasonably easy to analyze. For optimal performance (in efficiency or throughput) deviations from a design with coplanar layers may be necessary.

Both at the very small scales and at the very large scales a highly optimized nanofactroy design may strongly deviate from a simple stack of layers.

Some new factors that come into effect at large scales are:

- The production facilities own mass under earths (or other planetary) gravity

- At very large scales even abundant materials can get scarce.

- Warning! you are moving into more speculative areas.

At very very large scales production facilies would act as "planetoid" attracting the outer parts of its structure to its center.

Related: Look of large scale gem-gum factories

Degree, stepsize, fillfactor, ...

There are at least three important parameters to characterize convergent assembly.

- The "degree" or "convergent assembly depth" of convergent assembly, in terms of number of convergent assembly levels across the whole stack. Stacks of chambers of the same are counted as one layer! Such stacks need means to transport finished parts to the top. Convergent assembly depth has little effect on maximal throughput! But not none.

- The "stepsize" or "branching factor" of (convergent) assembly, in terms of the ratio of product-size to resource-size in each assembly step, has a huge effect on speed. Note though that this parameter is present for all "degrees" of convergent assembly even degree one or zero. Meaning it is also present in productive nanosystems that lack convergent assembly. (In systems with more than one convergent assembly layer unequal stepsizes can occur.)

- The "fillfactor" or "chamber to part size ratio". This is relevant for when the convergent assembly does not lead all the way up to a single macroscopic chamber but instead stops sooner. The topmost layer has to fill a dense volume unlike the layers below. If the topmost layer indeed assembles a dense product then this will slow it down (if not compensated by more and/or faster working sub-chambers in the layer below).

Influence of the degree of convergent assembly on throughput speed

Convergent assembly per se is not faster than if one would just use the highly parallel bottom layer(s) to assemble final product in one fell swoop. Assembling the final product in one fell swoop right from a naive general purpose highly parallel bottom-most layer would be just as fast as a system with the same bottom-layer that has a convergent assembly hierarchy stacked on top. There are indirect aspects of convergent assembly that provide speedup though. Including avoiding unnecessary energy turnover.

Especially recycling in the higher assembly levels should be able to give a massive speed boost.

Speedup of recycling (recomposing product updates) by enabling partial top down disassembly

- Simpler decomposition into standard assembly-groups that can be put together again in completely different ways.

- Automated management of bigger logical assembly-groups

Full convergent assembly all the way up to the macro-scale allows one to perform rather trivial automated macroscopic reconfigurations with the available macroscopic manipulators. Otherwise it would be necessary to fully disassemble the product almost down to the molecular level which would be wasteful in energy and time. In short: just silly.

Especially doing full disassembly at the lowest assembly levels makes the surface area explode and number of strong interfaces that need to be broken and reformed explode. Each step with a potentially very low but still existent efficiency penality. Getting energy in and waste heat out can limit operation speed.

Choosing to leave out just the topmost one to three convergent assembly layers could provide the huge portability benefit of a flat form factor (without significant loss of reconfiguration speed). Alternatively with a bit more design effort the topmost convergent layers could be made collapsible/foldable.

Convergent assembly makes low level specialization possible => speedup

Putting the first convergent assembly layers right above the bottom layers allows for specialized production units (mechanosynthesis cores specialized to specific molecular machine elements) that can operate faster than general purpose production units. The pre-produced standard-parts get redistributed form where they are made to where they are needed by an intermediary transport layer and then assembled by the next layer in the convergent assembly hierarchy.

Component routing logistics

Between the layers of convergent assembly there is the opportunity to nestle transport layers that are potentially non local.

If necessary the products outputted by the small assembly cells below the one bigger associated upper assembly cell may be routed beyond the limits of this associated assembly cell that lies directly above them. That is if the geometric layout decisions allow this (this seems e.g. relatively easy the case in a stratified nanofactory design). This allows the upper bigger assembly cells to receive more part types than the limited number of associated lower special purpose mill outputs would allow. The low lying crystolecule routing layer is especially critical in this regard.

Comparison to specialization on the macroscale

In today's industry of non atomically precise production convergent assembly is the rule but in most cases it is just not fully automated. An example is the path from raw materials to electronic parts to printed circuit boards and finally to complete electronic devices. The reason for convergent assembly here is that for the separate parts there are many specialized production places necessary. The parts just can't be produced directly in place in the final product.

Usually one needs a welter of completely identical building components in a product. Connection pins are a good example. Single atoms are completely identical but they lack in variety in their independent function. Putting together standard parts in place with a freely programmable general purpose manipulator amounts to a waste of space and time. General purpose manipulators are misused that way.

Even in general purpose computer architectures there are - if one takes a closer look - specially optimized areas for special tasks. Specialization on a higher abstraction level is usually removed from the hardware and put into software.

(In a physically producing personal fabricator there's a far wider palette of possibilities for physical specialization than in a data shuffling microprocessor since there are so many possible diamondoid molecular elements that can be designed.)

Bigger assembly groups provide more design freedom and for the better or the worse the freedom of format proliferation. Here the speed gain from specialization drops and the space usage explodes exponentially because of the combinatoric possibilities. Out of this reason this is the place where to switch hardware generalization compensated by newly introduced software specialization.

Thus In a personal fabricator the most if not all the specialization is distributed in the bottom-most layers. Further up the assembly levels specialization is not a motivation for convergent assembly anymore. Some of the other motivations may prevail. Higher convergent assembly levels (layers) quickly loose their logistic importance (the relative transport distances to the part sizes shrink). The main distribution action takes place in the first three logistic layers.

Side-notes:

- In the obsolete assembler concept all parts of a product where thought to be mechanosynthesized right at their final place in the product.

- Consumer side preferences in possibility space may drive higher level physical specialization in beyond advanced APM systems.

Characterization of convergent assembly

See: Math of convergent assembly

Convergent assembly can follow different scaling laws and follow different topology.

Depending on that the embedding of convergent assembly into 3D space sometimes necessarily need to change.

For artificial machine phase systems an organization of assembly levels into assembly layers seems to be the obvious starting point for design. When liquid or gas phase is involved then dendridic tree like designs that have too much branching to match a layered design might be the better choice.

Related

- Math of convergent assembly

- Convergent self assembly

- Visualization methods for gemstone metamaterial factories

In particular: Distorted visualization methods for convergent assembly - Level throughput balancing

- Assembly levels

- Assembly layers

- Multilayer assembly layers

- Fractal growth speedup limit

- relation to data packages in electronic networks

- Higher throughput of smaller machinery

(TODO: investigate various forms of self assembly further)

External links

- Convergent assembly can quickly build large products from nanoscale parts (from K. Eric Drexlers website)

- Illustrations: http://e-drexler.com/p/04/05/0609factoryImages.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Max-flow_min-cut_theorem and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Approximate_max-flow_min-cut_theorem

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maximum_flow_problem

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flow_network

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Circulation_problem

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mathematical_optimization